Corn

Use By The American Indian

Stalks, Leaves, and Husks. – The Indians commonly wasted the stalks, leaves, and husks except for a limited use in mats, beds, thatching, and fuel. In Mexico and parts of South America the large, outer husks were and are still used for wrapping tamales for cooking. The thin, inner husks were used for cigarette paper. Like its near relative, sugar cane, cornstalks produce sugar. Prescott writes of the Aztecs obtaining juice from the stem, which was boiled down to a syrup or fermented and used as a drink.

Ears and Kernels. – The roasting ear was everywhere a favorite food of the Indian. Com was eaten raw, boiled, or roasted, and the Indian invented the mixture of green corn and beans known as succotash. Parched com was widely known and used in many ways.

Meal. – Several different methods were used by the Indians in making corn meal. In Pennsylvania, a vessel containing sand was heated. The corn was then mixed with this sand and slowly heated until the grain burst. The burst grain was then taken out and ground to a fine powder. In another method the .corn was first parboiled, the water drained off, and the grain dried. The dried kernels were roasted on a plate, ashes being mixed with them to prevent burning. The grains were stirred constantly and soon acquired a red color, at which time they were removed and well rubbed. They were then mixed with the ashes of the dried stalk of the kidney bean, a little water was added, and the mixture thoroughly pounded into meal. Among the Indians of the southwestern United States, the blue com was used. This when rubbed in a stone mortar gave a meal of bluish-gray color. A second method used in this same section of the country was to cook the com in limewater until the hard covering was removed; then the grain was pounded into white flour. This last method is used by the white man in preparing hominy.

The food use of corn meal varied in different parts of the country. The various ways of making bread were as follows: in the neighborhood of Pennsylvania the meal was kneaded with water into dough. This dough was made into round cakes about six inches in diameter and about an inch thick. They were then baked in clean wood ashes. Dough was sometimes mixed with pieces of pumpkin, beans, chestnuts, huckleberries, etc. Indians also mixed smoked eels and shellfish, chopped fine, with their corn meal in the making of bread.

The mestizas of Mexico made similar corn bread in various shapes and sizes, known as gorditas. In the southwestern United States and Mexico thinner cakes called tortillas were also made. In their manufacture a thin batter was used, dipped from a bowl by the hands and spread in a thin layer on a hot stone or plate. The mass quickly puffs up, a sign that one side is done, and it is then turned over, while the second cake is placed on to bake. Thinner cakes were made of blue starch com by the Hopi Indians in Arizona. These thin cakes were rolled up like thin jelly rolls and were known as piki bread.

Pinole was corn meal cooked or mixed with sugar from the mesquite (Prosopis juliflora D.C) or other source. The Central American Indians added a red coloring matter, arnatto, to this mixture and called it yixte. In Mexico such a mixture without coloring matter was cooked and wrapped in small pieces of corn husk, in the form of a necklace, for ease of transportation when traveling. These were known as saules.

Various forms of pottage in which corn meal was the basis were familiar to the Indian. In the northeastern section of the country the meal was boiled with fresh or dried meat (the latter pounded), dried pumpkins, beans, or chestnuts. Sometimes the mixture was sweetened with maple syrup or sugar. An appetizing dish was made by boiling well-pounded hickory nut kernels with corn. In the southwestern United States and in Mexico meal was often cooked with pieces of meat with red or green peppers or other vegetable. When this is wrapped in corn husks and boiled it is known as a tamale. Bread was also made from crushed, fresh, undried corn.

Beverages. – Although the Indians realized the substantial way that corn supplied some of their essential needs, yet their keenest sense of pleasure came from the drinks that it afforded. They had a great many of these. One god is said to have given the Mexicans nine excellent recipes at one visit. Probably the most commonly used fermented drink was chicha, which was widely known in many forms. There were many ways of preparing it. The dry, parched, or sprouted com was either ground or masticated and then mixed with water and allowed to ferment. This was highly intoxicating.

The Use Of Stalks

Syrup. – Most of the different plants of the grass family have hollow stems, but there are three notable exceptions: sorghum, sugar cane, and corn. All three contain cane sugar. The Aztecs in Mexico made use of the corn plant for sugar, in the same manner as sugar cane is now used.

In a Minnesota experiments five varieties of sweet com and two of field com were used. When the com is ripe enough to can, the juice of the stalks contains 9-11 per cent cane sugar. If the stalks stand in the field twenty days after the removal of the ears, the amount of sugar in the stalk increases to 13-17 per cent. The proper stage for syrup-making is during the time of maximum amount of sugar in the juice, not only because of the yield but because of the quality of the juice. Cornstalk syrup may be manufactured by nearly the same process as sorghum syrup. Cornstalk syrup is clear, reddish amber in color, with a pleasant flavor. As produced, it is not a table syrup but an excellent cooking syrup considered equal to the best grades of sorghum and cane molasses

Camp Food

Taken From: The Book Of Camp-Lore And Woodcraft By Dan Beard

Parched Corn as Food

When America gave Indian corn to the world she gave it a priceless gift full of condensed pep. Com in its various forms is a wonderful food power; with a long, narrow buckskin bag of hoe cake, or rock-a-hominy, as parched cracked com was called, swimg upon his back, an Indian or a white man could traverse the continent independent of game and never suffer hunger. George Washington, George Rodger Clark, Boone, Kenton, Crockett, and Carson all knew the sustaining value of parched corn.

How To Dry Corn

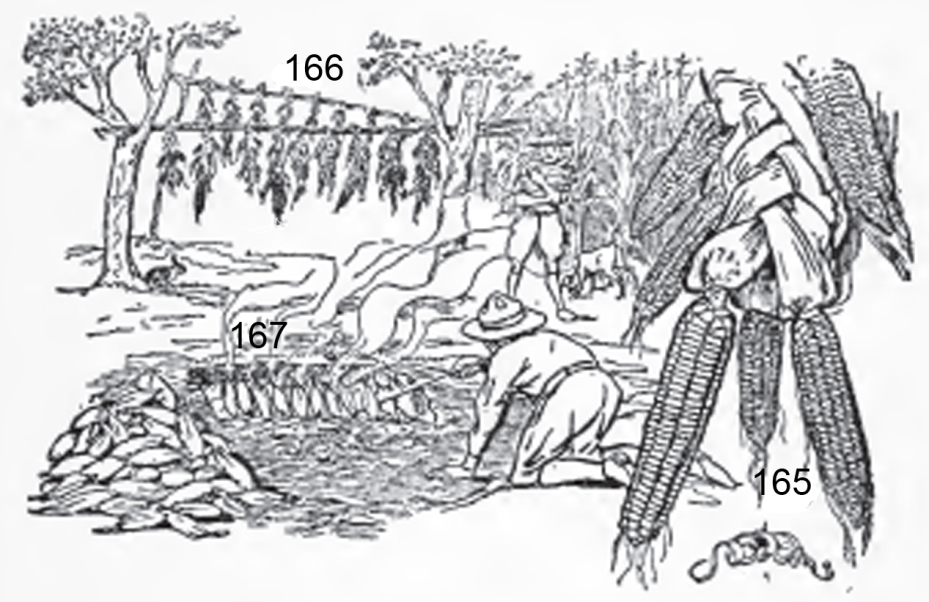

The pioneer farmers in America and many of their descendants up to the present time, dry their Indian corn by the methods the early Americans learned from the Indians. The com drying season naturally begins with the harvestingof the com, but it often continues until the first snow falls. Selecting a number of ears of com, the husks are pulled back exposing the grain, and then the husks of the several ears are braided together (Fig. 165). These bunches of corn are hung over branches of trees or horizontal poles and left for the winds to dry (Fig. 166).On account of the danger from corn-eating birds and beasts, these drying poles are usually placed near the kitchen door of the farmhouse, and sometimes in the attic of the old farmhouse, the woodshed or the bam.

Of course, the Indians owned no corn mills, but they used bowl-shaped stones to hold the corn and stone pestles like crudely made potato mashers with which to grind the com. The writer lately saw numbers of these stone corn-mills in the collection of Doctor Baldwin, of Springfield, Mass.

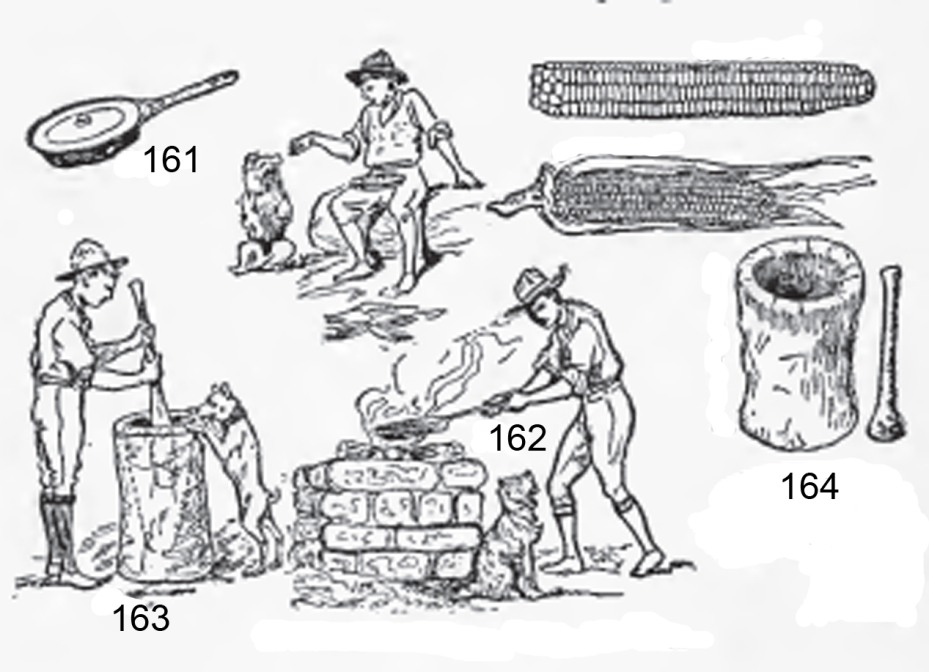

In the southwest much grit from the stone used is unintentionally mixed with the com, and hence as the elderly Indians' teeth are worn down as if they had been sandpapered. But the reader can use a wooden bowl and a potato masher with a piece of tin or sheet iron nailed to its bottom with which to crush the corn and make meal without grit. Or he can make a pioneer mill like Figs. 163 or 164, from a log.The pestle or masher in Fig. 164 is of iron.

Sweet Corn – There is a way to preserve corn which a few white people still practice just as they learned it from the Indians. First they dig long, shallow trenches m the ground, fill them with dried roots and small twigs with which they make a hot fire and thus cover the bottom of the ditch with glowing embers. The outer husks of the fresh green com are then remove and the corn placed in rows side by side on the hot embers (Fig. 167). This practice gave the name of Roasting Ear Season to July and August.

As the husks become scorched the ears are turned over, and when browned on all sides they are deftly tossed out of the ditch by means of a wand or stick used for that purpose. The burnt husks are now removed and the grains of com are shelled from the cob with the help of a sharp-edged, fresh water "clam" shell; these shells I have often found in the old camping places of the Indians in the half caves of Pennsylvania.

The corn is then spread out on a clean sheet or on pieces of paper and allowed to dry in the sun. It is "mighty " good food, as any Southern born person will tell you. One can keep a supply of it all winter.

Parched Field Corn

When I was a little shaver in old Kentucky, the children were very fond of the Southern field corn parched in a frying pan (Fig, 161), and then buttered and salted while it was still hot; we parched field com, sugar corn and the regular popcorn, but none of us had ever seen cracked corn or com meal parched and used as food, and I am inclined to think that the old pioneers themselves parched the corn as did their direct descendants in Kentucky, and that said corn was crushed or ground after it had been parched. Be this as it may, we know that our bordermen traveled and fought on a parched corn diet and that Somoset, Massasoit, Pocahontas, Okekankano, Powhatan, all ate corn cakes and that it was either them or the squaws of their tribes who taught bold Captain Smith's people on the southern coast, and the Pilgrims further north, the value of corn as an article of diet. The knowledge of how to make the various kinds of corn bread and the use of corn generally from "roasting-ears" to corn puddings was gained from the American Indians. It was from them we learned how to make the

Ash Cakes – This ancient American food dates back to the fable times which existed before history, when the sun came out of a hole in the eastern sky, climbed up overhead and then dove through a hole in the western sky and disappeared. The sun no more plays such tricks, and although the humming-bird, who once stole the sun, still carries the mark under his chin, he is no longer a humming-birdman but only a little buzzing bird; the ash cake, however, is still an ash cake and is made in almost as primitive a manner now as it was then. Mix half a teaspoonful of salt with a cup of corn meal, and add to it boiling hot water until the swollen meal may be worked by one's hand into a ball, bury the ball in a nice bed of hot ashes (glowing embers) and leave it there to bake like a potato. Equaling the ash cake in fame and simplicity is Pone.

Pone – is made by mixing the meal as described for the ash cake, but molding the mixture in the form of a cone and baking it in an oven.

Johnny–cake – Is mixed in the same way as the pone or ash cake, but it is not cooked the same, nor is it the same shape; it is more in the form of a very thick pancake. Pat the Johnny-cake into the form of a disk an inch thick and four inches in diameter. Have the frying pan plentifully supplied with hot grease and drop the Johnny-cake carefully in the sizzling grease. When the cake is well browned on one side turn it and brown it on the other side. If cooked properly it should be a rich dark brown color and with a crisp crust. Before it is eaten it may be cut open and buttered like a biscuit, or eaten with maple syrup like a hot buckwheat cake. This is the Johnny-cake of my youth, the famous Johnny-cake of Kentucky fifty years ago. Up North I find that any old thing made of com meal is called a Johnny-cake and that they also call ashcakes "hoe-cakes," and com bread "bannocks," at least they call camp com bread, a bannock. Now since bannocks were known before corn was known, suppose we call it Camp Corn Bread and Corn Dodgers.

In the North they also call this camp com bread "Johnnycake," but whatever it is called it is wholesome and nourishing. Take some corn meal and wheat flour and mix them fifty-fifty; in other words, a half pint each; add a teaspoon level full and a teaspoon heaping full of baking powder and about half a teaspoonful of salt; mix these all together, while dry, in your pan, then add the water gradually. If you have any milk go fifty-fifty with the water and milk, make the flour as thin as batter, pour it into a reflector pan, or frying pan, prop it up in front of a quick fire; it will be heavy if allowed to cook slowly at the start, but after your cake has risen you may take more time with the cooking. This is a fine corn bread to stick to the ribs. I have eaten it every day for a month at a time and it certainly has the food power in it. When made in form of biscuits it is called "corn dodgers.”