The Language Of Footprints

Taken From: Indian Scout Talks

By: Charles A. Eastman (OHIYESA) © 1914

You have often heard it said that " actions speak louder than words." It is a fact that both voluntary and involuntary actions of the body tell truly the mind's purpose, and this is why the Indian studies so assiduously every record of the comings and goings of his fellow creatures, both animal and human. The footprint, I want you to bear in mind, is first of all a picture of all the prominent points on the sole. The ball of the foot, the heel and toes, hoof and claw, each makes its own impress. Even the fishes make theirs with their fins, which to them are hand and foot. This is the wood-dweller's autograph. More than this, each series of footprints tells a bit of history perhaps betrays a secret to the instructed eye, and the natural Indian did not neglect to drill his child thoroughly in this important branch of learning.

I will now ask you to enter the forest with me. First, scan the horizon and look deep into the blue vault above you, to adjust your nerves and the muscles of your eye, just as you do other muscles by stretching them. There is still another point. You have spread a blank upon the retina, and you have cleared the decks of your mind, your soul, for action.

Let us divide our scouts into small groups; one alone is sometimes best, when you are pretty well advanced in this study, but at first two or three, with a head scout or teacher, will do. We will assume that you have passed the primary test; that is, you have learned to recognize the foot- prints of mice, birds, squirrels, rabbits, and perhaps to some extent the next set, those of the dog, the cat, the fox, and the wolf.

It is a crisp winter morning, and upon the glistening fresh snow we see everywhere the story of the early hours – now clear and plain, now tangled and illegible – where every traveler has left his mark upon the clean, white surface for you to decipher.

The first question is: Who is he? The second: Where is he now? Around these two points you must proceed to construct your story.

If the snow is not deep, the imprint of the toes and even the claw marks are very distinct, but in deep, soft snow you have only the holes made by the foot and leg. Some animals, such as the cow, drag their feet, while the wolf kind make a mark much like the print of a cane. This is also true of the cat family. The distinguishing difference is in the gait, as shown in the relative position of the footprints, and this is a matter that calls for careful attention. The break in each print is usually greater behind than before, and this tells you in which direction the animal is going.

The rabbit makes innumerable tracks as soon as it stops snowing, and we may be sure that its burrow is not far distant, for unless food is scarce or danger imminent, they will not leave their own immediate locality. As to larger animals, love-affairs often lead them far afield, and wolves and bears cover much ground; yet even they have their favorite haunts, and they are masters of their map. All these things the student of footprints should bear in mind.

It is essential to estimate as closely as you can how much of a journey you will undertake if you determine to follow a particular trail. Many factors enter into this. When you come upon the trail, you must if possible ascertain when it was made. Examine the outline; if that is undisturbed, and the loose snow left on the surface has not yet settled, the track is very fresh, as even an inexperienced eye can tell. Next determine the sex, and finally the age, if you can: all these enter into the problem of getting your game. It is easy to tell the sex of the deer family by their footprints; the female has sharper hoofs and a narrower foot, while the male has rounded points to the hoofs.

It will also be necessary to consider the time of year. It is of no use to follow a buck when he starts out on his travels in the autumn, and with the moose or elk it is the same. If the track is a running one, the question is: Was it in play or in flight? Look at the toes; if they are widely spread, he was running for sport and exercise; if close together, it was a race for life.

Many animals for safety's sake go through a series of maneuvers before they lie down to rest. For instance, at the end of the trail they make two loops, and conceal themselves at a point where the pursuer must, if he sticks to the trail, pass close by their hiding-place and give timely warning of his approach. This trick is characteristic of the deer and rabbit families.

The tracking of an animal in summer is naturally much more difficult than in winter, unless the footprints are on soft ground. The Indian hunter is then even keener in his observations; he looks for the displacement of leaves and blades of grass, or for broken dry sticks. These slight displacements will adjust themselves in a short time, to be sure; but in hunting, the fresh track is what is wanted. Other tracks are not much followed, except those of man or bear from whom danger is to be feared. A new trail, especially one made during a dewy night, is easy to trace the next morning, and on the open prairie the reflection of sun on the grass blades helps, so that sometimes a few paces away one may see the trail clearly.

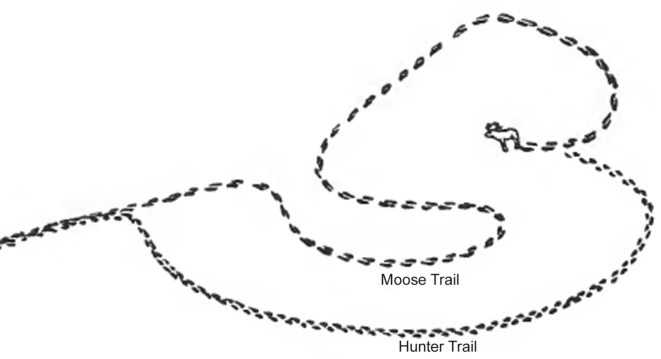

Referring to winter trailing, I remember well an example of perfect accuracy set by my uncle, who was a famous hunter. I was then a boy of about fifteen, living in the wilds of Manitoba. We came suddenly upon a moose track, evidently made on the day before, as the upturned snow was frosted over by a night's cold. He stopped and surveyed the lay of the country. A little way ahead a ravine led down to a lake, of which the outlet was densely wooded with willows and birches. We followed the trail down the ravine and along the lake shore until we reached this stream, and here my uncle paused and climbed a tree. When he came down, he examined his gun and put in a fresh load, then proceeded cautiously a few paces, when we came upon another trail crossing the first almost at right angles. It, too, was a day old. To my surprise, my uncle now motioned to me to stay where I was, and throwing off some of his garments and adjusting his moccasins, he ran back on his trail. I waited about half an hour, when I heard the report of his gun, and soon after he returned with the good news: "I got him!"

The diagram shows you how it was done. The moose had covered his position by a swinging loop, and was lying down facing the first turn. At that time of year they may remain thus for several days. He had seen that we did not enter the loop and felt safe. My uncle, knowing the trick, had run back a hundred yards or so, then circled behind the loop, and approached him from the rear, where he easily brought him down.

Hunter's Trail

Figure 1

Among the Indians, the study of human footprints was carried to a fine point. Many of us would be able to say at a glance, Here goes So-and-So, with perfect accuracy. Even the children would recognize instantly the footprint of a stranger from another tribe. It was claimed by some that character may be read from the footprint, just as some white people under- take to read it from the handwriting, on the ground that certain characteristic attitudes and motions of the body, reflecting mental peculiarities, affect the gait and consequently the pedal autographs. At any rate, our people are close readers of character, and I do not hesitate to say that faithful study of the language of foot-prints in all its details will be certain to develop your insight as well as your powers of observation.